THE STRANGE WOMAN

CATEGORY: LATE CHILDHOOD

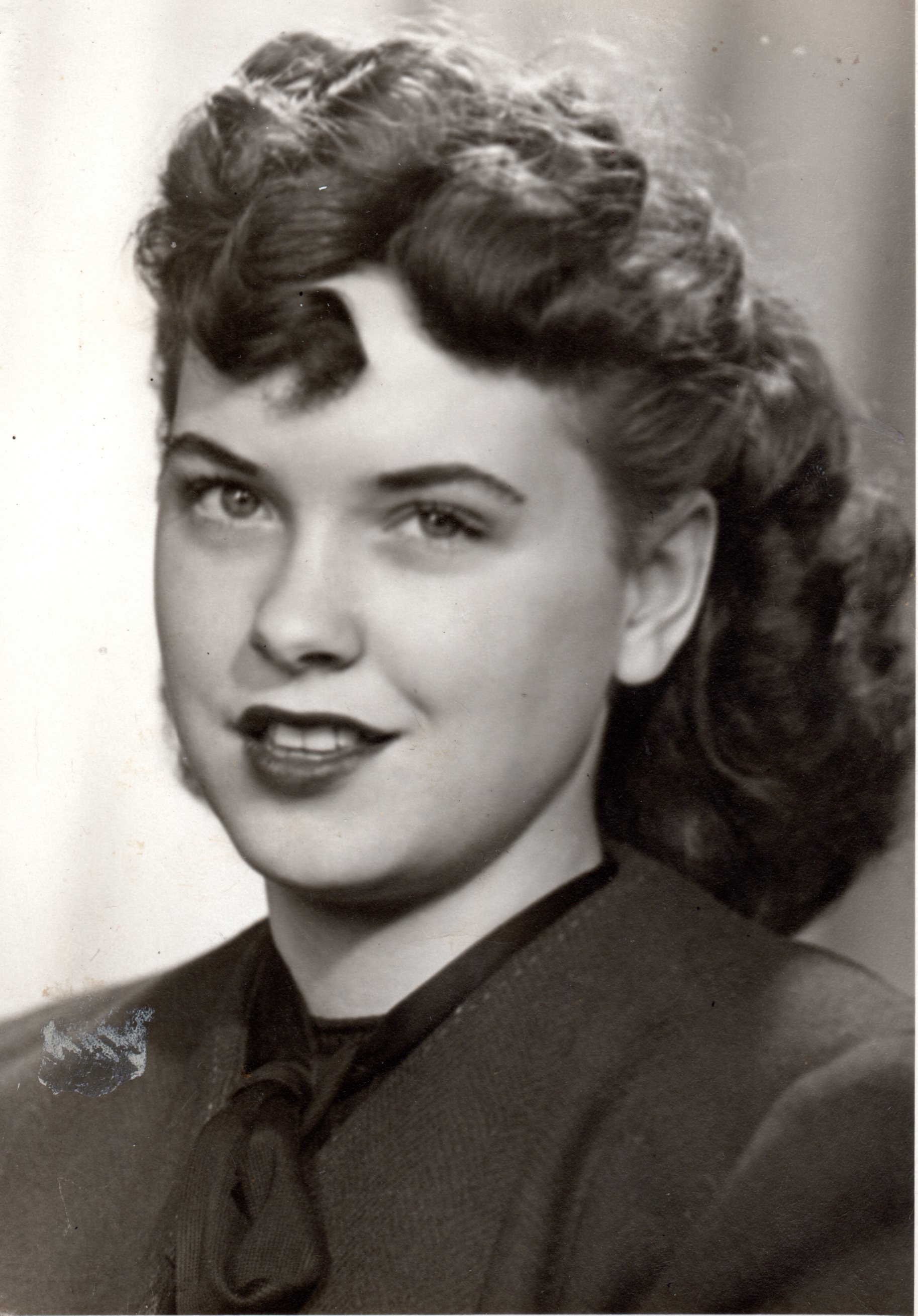

PHOTO: MARY AT FOURTEEN

In the spring of 1944, I graduated from the eighth grade in Grass Valley. Mary had spent that year of her high school education in Lakeview living with our father. I missed her terribly, as did our mother. She was not as “wild” as I was, meaning that she did not ride horses standing up bareback and climb to the top of the highest tree. She had been a calming influence in our childhood, although just before she left for Lakeview, she had had her own wild moments. One of them was that she had read a book entitled THE STRANGE WOMAN about a beautiful woman with whom men fell violently in love and how she had no mercy but laughed at them in scorn. Mary told me that she was like that woman—that several men had been in love with her and that she hated them all. She told this to me in confidence when she was thirteen and I was twelve. Mary’s kind of “wild” was something I had never even imagined: flirting outrageously with boys: kissing an old drunken sheep herder on the lips when we lived in Shaniko!

In the spring of 1944, I graduated from the eighth grade in Grass Valley. Mary had spent that year of her high school education in Lakeview living with our father. I missed her terribly, as did our mother. She was not as “wild” as I was, meaning that she did not ride horses standing up bareback and climb to the top of the highest tree. She had been a calming influence in our childhood, although just before she left for Lakeview, she had had her own wild moments. One of them was that she had read a book entitled THE STRANGE WOMAN about a beautiful woman with whom men fell violently in love and how she had no mercy but laughed at them in scorn. Mary told me that she was like that woman—that several men had been in love with her and that she hated them all. She told this to me in confidence when she was thirteen and I was twelve. Mary’s kind of “wild” was something I had never even imagined: flirting outrageously with boys: kissing an old drunken sheep herder on the lips when we lived in Shaniko!

Coming home from one of my last days at school, I walked into the house to find Mother crying uncontrollably, holding a letter in her hand. I tried to comfort her, but she could not be comforted. She was finally able to gasp out between sobs that Mary had met a cowboy from Paisley who was twice her age and had married him. Being twice her age did not make him very old since she was only fourteen at the time of the marriage. I asked how that could have been possible without her mother’s consent (even I knew that much). She said that Daddy had given her his consent. She showed me the letter that she had just received from him. It was pure vindictiveness. It was easy to read between the lines that he had given Mary his permission just to get even with Mother for her having “deserted” him. He completely ignored her reasons for having gone back to work: that he was out of a job with no prospects of getting another, that our family was penniless and that the first job she could get was in Camp Sherman. He clearly cared more about his own damaged feelings than he did about his daughter’s welfare. He said that he “wanted Mary to be happy,” but he also indicated that this “older man” would “know how to handle her,” as if she had given Daddy some trouble, and he wanted her disciplined.

At this, I started to cry too. It seemed like we had touched hands with some crude and sharp edged world that had no place in our lives, and that my sister was lost to us forever. Mother and I held each other and cried out our misery. But when we were through crying, the misery did not go away.

A year later Mary came home for a visit with her three month old daughter. She had dyed this infant’s hair. Red. She said that she had always hated her own brown hair, that she wished her hair had been red, and that if she dyed the baby’s hair red from the beginning, people would think it had been born with red hair.

A couple of years later, when she was newly seventeen, Mary came home to our mother, then living in Moro. She was getting a divorce. Her husband’s sister was going to take the baby and raise it as her own. Mary had grown into a beautiful woman. She dyed her own hair red and got a job in a local bar, probably by lying about her age. Her life from then on was as foreign to me as someone who was living on the moon. Later she became unrelentingly religious. She was unforgiving of any woman who was sexually promiscuous. She was rabid against abortion. She said that if any girl got pregnant out of wedlock, she should have to have the baby as a punishment.

I must add though that she was always kind and generous to those in need, especially children and elderly women–and especially to women who were hard working and abused by their husbands. Mary was hard working herself, although not abused by her husband, at least not the first one. He was always good hearted but confused and in shock by his brief marriage.

Mother told me much later that when Mary came home, she had confided the reason for her divorce. She told mother that she had not understood that sex was a regular part of marriage. She thought it happened only when a couple wanted a baby. She said she hated it and could not stay married. Mother blamed herself for not being clear about this when she told us about the birds and the bees. I told her it was not her fault. Who would know that Mary would hate marital intimacy, and that her husband, raised in the outback, was probably as ignorant as she was about love making? Mary told me once when she was in her fifties and had been married three times, that she had never had an orgasm.

Her child is my niece, Dawn, who became reconnected with our family after she herself was married. She looks like Mary. She doesn’t have red hair.